The lived house

Tile panel. Iznik, Turkey. Imperial workshop. Around 1573. Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian/ Museu Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisbon.Foto: Carlos Azevedo

Fragment of wall tiling. Antoni Maria Gallissà (1861-1903). Jaume Pujol i Bausis & Sons ceramics factory. Esplugues de Llobregat, around 1900

Museu del Disseny de Barcelona. Photo: Guillem Fernández Huerta

Tiles. Fábrica B. Santigós y Cía, Madrid, 1877-1892. Museu del Disseny de Barcelona. Photo: Guillem Fernández Huerta

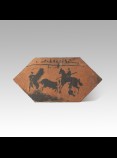

Tiles. L’étoile du mer, Flèches, Pigeons, Le sol vegetal, Le baiseur du feu and Les guitarres, 1954. Salvador Dalí for Onda’s ADEX factory (Valencia). Lluís Maria Llubià donation, 1963.Museu del Disseny de Barcelona. Photo: Guillem Fernández Huerta

Fragment of the ceramic roof of the old Santa Caterina market in Barcelona. Ceràmica Cumella, 2004. Ceràmica Cumella, Granollers, Barcelona

Photo: Vicente Zambrano

Tiling. La Alhambra, Granada. Nassarite period, 14th century XIV. Museo de la Alhambra, Patronato de la Alhambra y Generalife, Granada

Mosaic. La Alhambra, Granada. Nassarite and Mudéjar periods, 14th-16th century. Museo de la Alhambra, Patronato de la Alhambra y Generalife, Granada.

Tile. Iran, 13th century. Porcelain decorated with lustreware and blue in a star pattern. Musée du Louvre, Département des Arts de l´Islam, Paris © Musée du Louvre, dist. RMN - Grand Palais / Raphaël Chipault

Vitrified ceramics brings physical and mental comfort to those who live with them: it attracts the senses and the imagination. It imbues interiors with sensory qualities that are pleasant to touch and see, and allows us to recreate brilliant worlds that are either visible or invisible, real or imaginary by means of painted or moulded panels that ensure the inhabitants feel a sense of well-being in their new paradise.

This technique was discovered in Egypt and Mesopotamia in the 3rd millenium BC. Pieces of terracotta covered with silica and pigments were crystallised after a second high-temperature firing. The interiors of Persian palaces were decorated with relief glazed panels that were more resistant than frescoes and tapestries. Via their Hispano-Muslim workshops, the Arab conquests spread a technique that allowed adobe walls to be decorated. Thanks to the Silk Road the contacts between Persia, China (where tin-glazed porcelain and the intensive use of cobalt blue were found - when melted, tin creates a brilliant white layer that can be painted with pigments) and Italy helped the tile to become popular from the European Renaissance onwards.

These smooth, shiny surfaces composed panels that resembled windows framing paradisical scenes. The geometric motifs and the orthogonal frames ordered the space and religious inscriptions, and heavenly figures protected the interior that became images of Eden. In addition, the ambient, light and visual comfort depicted also evoked the lands of our origins or heaven.

Modernista architects recreated dream-like Oriental buildings and an invented Middle Ages with tiles that fled from the industrial greyness of the time. The cold, abstract and immaculate look of white tiles contributed to modern architecture’s vocation of hygienism, disinfected of references to the past, albeit today coloured tiles once more help to integrate de-contextualised buildings into their surroundings and the sky above.

However, tastes for certain materials and manual techniques have encouraged some artists and architects to draw or paint limited edition or unique tiles or bricks in collaboration with professional ceramicists; examples of this are Rouault, Picasso, Dalí, Matisse or Miró, who affirmed: ‘I wish to bring ceramics into the home, there where humans live, something already done in very sunny countries where the light plays with ceramics.’